🎶 Introduction

Sufi chant encompasses the devotional musical practices linked to Sufism—the mystical dimension of Islam. For over a millennium, Sufis have expressed their quest for the Divine through:

- Sung poetry

- Rhythmic litanies

- Ecstatic dances

From the shores of the Middle East to the far reaches of South Asia, from the Maghreb to sub-Saharan Africa, these mystical songs have evolved into rich regional traditions. Yet all share a common spiritual aim:

« To invoke the presence of God in the hearts of the faithful through sacred music and poetry. »

This article invites you on a journey through the global history of Sufi chant, from:

- Its origins in the Middle East

- Its development within mystical brotherhoods (tariqas)

- To its worldwide diffusion in contemporary times

🧭 What You’ll Discover:

- Theological issues and controversies

- A comparison of major regional traditions:

- Indo-Pakistani Qawwalî

- Whirling dervish Samâ‘

- North African Gnawa rituals

- Arab Madîh and Inshâd

- An analysis of musical particularities:

- Modes (maqâm, râga)

- Rhythms, improvisation, instruments

- Languages and poetic structure

- An exploration of spiritual and social functions:

- Mystical trance

- Oral transmission and collective memory

- Communal and intercultural roles

- A look at contemporary evolutions:

- International festivals and artists

- Modern musical hybridizations

🧭 1. Origins and Historical Spread of Sufi Chant

📜 1.1 General Chronology

The roots of Sufi chant trace back to the early centuries of Islam. As early as the 8th century, Muslim ascetics began incorporating psalmody and singing into their spiritual practices.

« The practices of samâ‘ (mystical audition) and dhikr (litany) developed as early as the 8th century. » — Fritz Meier, cited by Tanvir Anjum

By the 11th–12th centuries, Sufism had become organized into brotherhoods (tariqas) throughout the Islamic world. Key figures like Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī (1058–1111) justified mystical music in their writings, arguing that, under certain conditions, listening to sacred poetry could elevate the soul toward God.

In Persia and Central Asia, the disciples of Ahmad Yasawī (12th century) chanted his hikmet (spiritual poems) in the Turkic language, laying the foundation for a tradition of Turkic mystical song.

🕰️ 1.2 Medieval Spread (13th–16th Centuries)

In the 13th century, Sufi chant experienced significant growth, driven by the expansion of Sufi brotherhoods and the wider spread of Islam.

- In Anatolia, the Persian poet Jalāl ad-Dīn Rūmī (1207–1273) inspired the founding of the Mevleviye order (Whirling Dervishes). His disciples developed the Mevlevi samâ‘, rituals combining chant and whirling ecstatic dance.

- In Northern India, masters of the Chishtiyya order such as Moinuddin Chishti (1142–1236) introduced samâ‘ as a means of reaching divine ecstasy. His disciple, poet-musician Amir Khosrow (1253–1325), created the Indo-Persian form of Sufi chant known as qawwalî in Delhi.

- The Chishti Sufis used chant to reach people’s hearts. Sessions were held in Ajmer and Delhi where Persian qasîdas resounded in the khanqahs (Sufi lodges).

In Central Asia and Persia, brotherhoods like the Naqshbandiyya, Qadiriyya, and Yasawiyya transmitted Persian chants accompanied by instruments like the oud, rebab, and ney flute.

In the Maghreb, Sufism spread via the Shādhiliyya order (13th c.). Dhikr and praises of the Prophet were sung in North African zawiyas (Sufi lodges). The famous Qasîdat al-Burda by al-Busīrī was recited during the Mawlid (Prophet’s birthday).

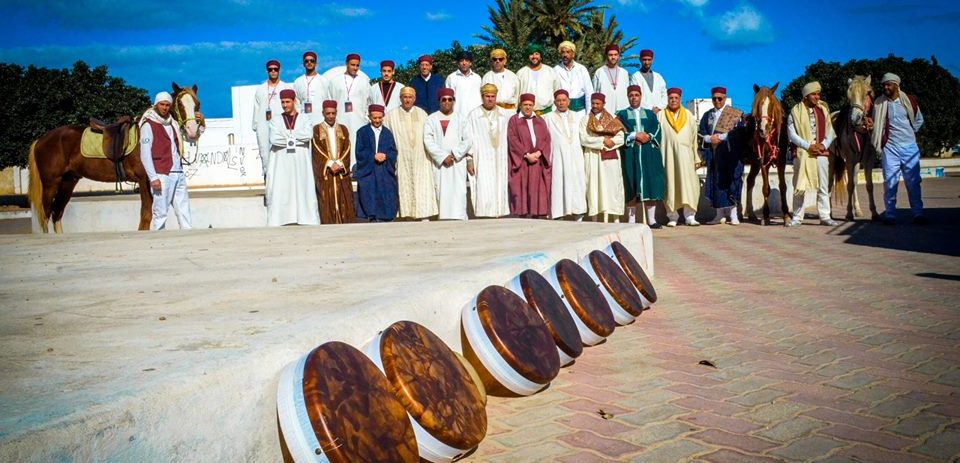

In Morocco, the Aïssawa brotherhood emerged in the 15th century around Sidi Mohamed Ben Aïssa (1465–1526), mixing rhythmic chants, percussion, and oboes to induce trance.

Simultaneously, the trans-Saharan slave trade (15th–17th c.) introduced West African influences into the Maghreb, giving rise to the Gnawa culture—born of a fusion between African ritual and classical Sufism. The lîla gnaoua ritual involves an all-night trance ceremony invoking spirits (mlûk).

📆 1.3 Modern and Contemporary Era

Between the 17th and 19th centuries, Sufi chant remained vibrant but had to adapt to new political and religious contexts:

- In the Ottoman Empire, Sufi brotherhoods were integrated into the social fabric. The Mevlevis of Istanbul became court musicians, composing ilahi and ayin in classical Turkish maqâms.

- In West Africa, Sufism spread through the Tijâniyya (c. 1780) and the Mourîdiyya (1883, Senegal). Their disciples sang in Arabic or Wolof in praise of God and Sheikh Ahmadou Bamba. These chants combined Arab-Andalusian modes (maqâm) with local vocal styles (powerful voices, heavy ornamentation).

- In Mughal India (16th–18th c.), qawwalî thrived under imperial patronage. Even Emperor Aurangzeb composed devotional na‘at.

- In Persia and Central Asia, despite political pressures, Sufi chant survived through madâh (praise songs) and zikr circles.

📀 1.4 20th–21st Century: Between Decline and Revival

The 20th century saw institutional setbacks:

- Modernist reforms

- Colonialism

- Banning of Sufi orders in Turkey (1925)

Paradoxically, Sufi chant survived through popular festivals, moulids (religious celebrations), and private spaces.

→ From the 1970s onwards, a global revival took place thanks to:

- Phonographic recordings

- International tours

🎤 Pakistani icon Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan (1948–1997) became a qawwalî legend, introducing this music to the global stage.

- Whirling dervishes resumed performances (Turkey, 1950s) in cultural formats.

- New Sufi music festivals emerged:

- ✨ Festival of Sacred Music in Fes (Morocco, 1994)

Sufi chant entered the realm of world music: → Sufi jazz, Sufi rock, electro-spiritual fusions

Today, Sufi chant serves as:

- A vector of spiritual heritage for future generations

- A living ritual within brotherhoods

- A globalized artistic expression

🌍 2. Major Regional Traditions of Sufi Chant

🇮🇳 Qawwali – South Asia Qawwali is the most emblematic form of Sufi chant in the Indian subcontinent (Pakistan, North India). Originating in the 13th century within the Chishtiyya order, it draws from Persian and Hindustani poetry.

🧑🎤 Ensemble Composition A qawwali party typically includes:

- 1 or 2 lead vocalists (qawwâl)

- A chorus responding in echo

- Musicians playing harmonium, tabla, and dholak Originally, Chishti Sufis performed a cappella or with simple percussion. For instance, Nizamuddin Auliyâ forbade instruments during his samâ‘ sessions.

🎶 Traditional Performance Structure

- Qaul: prophetic sayings as sacred prelude

- Hamd: praise of Allah

- Na‘at: praise of the Prophet

- Manqabat: chants for ‘Ali or the saints

- Mystical ghazals: in Urdu, Persian, or Punjabi

The ghazal, a poetic form of mystical love, allows qawwâls to repeat key lines, enhancing the incantatory effect. Rhythmic crescendos and head movements aim to induce wajd (spiritual ecstasy).

Profane love metaphors (intoxication, passion) are often used to express divine experience.

📝 Notable Poets

- Amir Khosrow (founder of the genre)

- Bulleh Shâh (Punjabi, 18th century)

- Various mystics exalting maḥabba (divine love)

📍 Context and Evolution Qawwali was traditionally performed in dargâhs (Sufi shrines), especially during ‘urs (saints’ anniversaries). Today it also features:

- At Sufi mausoleums (e.g., Nizamuddin Auliyâ in Delhi)

- On global stages (Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan) Current performers include the Sabri Brothers and Abida Parveen.

Samâ‘ and Sema – Turkey and the Balkans Samâ‘ (mystical audition) takes a specific form in the Mevleviye order (“whirling dervishes”), founded in Konya in 1273 around Rûmî.

💃 The Mevlevi Sema Ritual

- Ecstatic dance: dervishes spin around their master (the sun), arms extended

- Symbolism: white robe = shroud / felt hat = tombstone of the ego

- Purpose: divine ecstasy and imitation of cosmic motion

🎼 Music and Structure The repertoire, called Âyin, includes:

- 4 alternating sections (chant/interludes)

- Multiple maqâms Instruments:

- Ney (reed flute), symbolizing divine breath

- Kudüm (kettledrums), zils (cymbals), tanbûr, qanûn

- Chorus + ilahî (mystic hymns of Rûmî, Yunus Emre…) The ritual begins with Devr-i Veled (rotational greeting) and climaxes with a faster final section, followed by mystical silence.

⚖️ Modern History

- Banned in 1925 (secular Turkey), later tolerated (1950s)

- Today:

- Often folklorized for tourism

- Preserved by authentic Mevlevi groups Other orders in Turkey/Balkans: Bektashis, Halvetis, Alevis (cem ceremonies with saz chants)

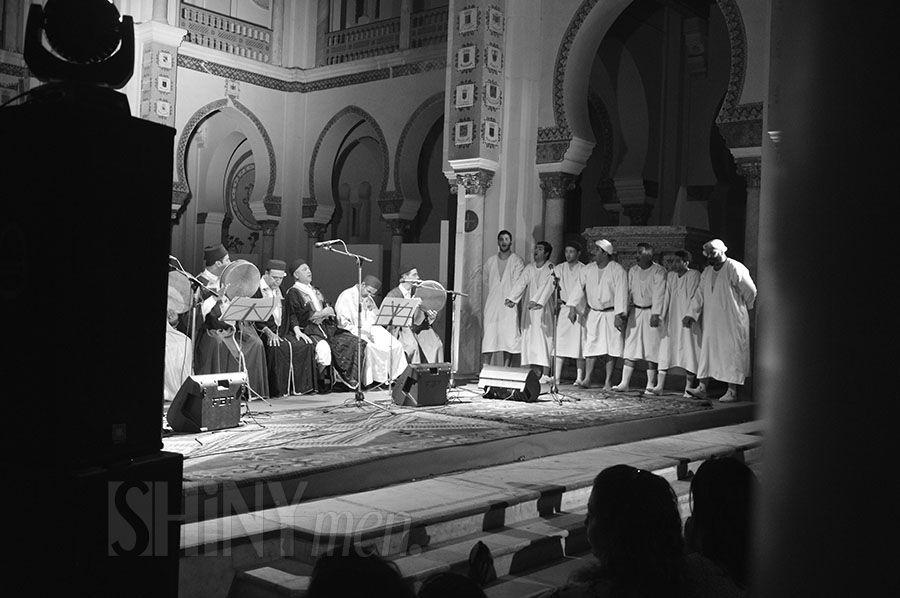

Madîh and Inshâd – Arab World 🌟 Madîh Nabawî A genre of praise for the Prophet, originating in the 7th century and developing with Mawlid (Prophet’s birthday).

- Soloist (munshid) + chorus + duff (frame drum)

- Dialogic structure: improvised verses + repeated refrains

- Maqâm modulation

- Collective fervor: chorus enhances the lead singer’s ecstasy

🎶 Regional Styles

- Maghreb: close to Andalusian nûba

- Egypt: dur form in sikah, bayati maqâms

- Syria: muwashshahât, qasâ’id in Aleppo/Damascus

- Iraq: Iraqi maqam Poetic sources: Arab Sufi poetry (e.g., al-Jazûlî, Dalâ’il al-Khayrât)

🪘 Special Case: Sudanese Madîh

- Poet: Hajj El-Mahi (c. 1780–1870)

- Two alternating male soloists

- Accompanied by târ drums

🎤 Inshâd and Nashîeîd

- Inshâd: traditional Sufi religious chant

- Nashîd Islâmî: modern spiritual hymns without instruments Famous recordings: al-Fashni, Aleppo traditions

Gnawa – Maghreb & West Africa Gnawa heritage stems from a blend of Sufism and sub-Saharan cultures. It originated from Islamized former slaves from Mali, Songhai, etc.

🌙 Central Ritual: The LîLa (or derdeba)

- All-night trance led by a maâlem (master musician)

- Chant sequences for each spirit (mlûk)

- Hypnotic repetition leading to possession

- Each suite marked by a specific color and rhythm

🧐 Instruments

- Guembri: 3-stringed bass lute

- Qraqeb: metal castanets

- Sometimes: tbel (large drums)

💠 Symbolism

- Invocation of saints, spirits, Prophets

- Aims: healing, purification, remembrance of slavery Today: performed at moussems and at the Gnaoua Festival of Essaouira

Issawa and Maghrebi Confraternities 🙌 Tariqa Aïssawa (founded 15th c., Meknès) Rituals include:

- Zbâr / psalmodic dhikr

- Tbol / bendir drums

- Ghaita (piercing oboe)

- Alternation of sacred words and ecstatic dance Some devotees enter spectacular trance (dancing, trials)

🎼 Musical Influences

- Andalusian (nûba)

- Sub-Saharan (Gnawa rhythms)

- Eastern (madîh) A living tradition in Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria (sometimes outside ritual settings)

🏨 Dhikr & Hadra – Islamic World Dhikr (remembrance) lies at the heart of universal Sufism.

🔀 Forms of Dhikr

- Collective repetition of divine names (Allah, Lâ ilâha illâ Allah)

- With or without percussion (duff)

- Gradual rhythm, deep breathing → Can induce ecstasy or mystical rapture

🌍 Geographic Variations

- Syria/Iraq: seated circles, rhythmic chant

- Gulf/Yemen: samâ‘ without instruments

- Turkey/Egypt: danced dhikr (sonorous breath)

- Chechnya: rotating trance circles

- Southeast Asia: Zikr Hadrah, drum-led chants

- Chinese Hui: Arabic zikr with local melodies

🌟 Spiritual Goal « Repeated Sufi chanting creates sonic vibrations that heal and uplift the soul. » — Egyptian practitioner

Hadra refers to the moment of divine presence: tranquility, tears, or exaltation.

→ Despite regional differences, these traditions share a common essence: chant that unites music, ecstasy, and spiritual memory, transcending borders and centuries.

🎼 3. Musical Characteristics of Sufi Chant

🎶 3.1 Modal Systems (maqām, rāga)

Sufi chants are grounded in the musical modes specific to each culture, offering each tradition a unique spiritual color.

- In Arab-Persian and Turkish regions: maqām (melodic modes of the East) are used.

Examples: maqām bayātī (gentle, mystical) for a Syrian madīh; maqām ḥijāz (poignant) in Morocco. - In North Africa: the tab‘ system, derived from Andalusian nūba, is commonly used.

- In South Asia: Indian rāgas are the basis, each associated with a specific mood or time of day.

Examples: rāga Bhairav (serene, morning), rāga Bhairavi (emotional, evening). - In Bosnia: Sufi ilahi sometimes incorporate local modal scales.

🎵 Each mode is intended to elevate the soul: emotional ecstasy (ṭarab) in maqām, expansive effect in rāga…

🥁 3.2 Rhythms and Temporal Cycles

Rhythm is essential to:

- Structure the performance

- Guide participants toward trance

🌀 Examples of rhythmic cycles:

- Qawwalī: Indian tāl cycles (e.g., 16-beat teentāl, 7-beat rūpak)

- Mevlevi: long cycles (e.g., 28/4, 14/4) encourage introspection

- Gnawa: polyrhythmic ostinatos in 2/4 or 6/8 with qraqeb castanets

⏳ Typical progression:

- Slow start: invocation or poetry

- Gradual rhythmic acceleration

- Sudden pauses or bursts to stimulate the soul

🌀 Some forms are unmeasured:

- Munājāt (Persian supplications)

- Taqsīm (Turkish instrumental preludes)

These moments of « float » create contemplative space before the rhythmic pulse resumes.

🌐 3.3 Languages and Poetry

Sufi chant embraces the linguistic diversity of mystical Islam.

📚 Main languages:

- Arabic (classical & dialectal): for dhikr, madīh, qasā’id

- Persian: Rūmī, Ḥāfeẓ, Sa‘dī, ‘Aṭṭār (from Kurdistan to the Caucasus)

- Turkish: Yunus Emre, Nesimî (sources of ilahis and nefes)

- Urdu, Punjabi, Saraiki: qawwalī repertoire

- Wolof, Swahili: confraternal chants in Africa

(e.g., Mourides in Senegal sing in Wolof-Arabic the khassā’id of Cheikh Bamba)

✍️ Oral Transmission:

- Spontaneous translations, dialect insertions

- Adapting the message to the listener’s heart-language

🎙️ 3.4 Improvisation and Ornamentation

Improvisation is a refined art in Sufi music.

💡 Vocal improvisation:

- Melodic variations (tankarana, sargam)

- Expressive repetition of key verses

- Improvised passages in dialect

🎤 In wajd (ecstasy), inspiration flows from the heart, not the intellect

💡 Instrumental improvisation:

- Taqsīm on ney, oud, rebāb

- Alāp (free intro) in Indian qawwalī

💠 Frequent vocal ornaments:

- Melismas, trills, appoggiaturas

- More restrained in Turkish ilahis

- More exuberant in Punjabi qawwalī or Aïssawa chants

🧱 3.5 Structure of Pieces and Performances

Despite the space for improvisation, each tradition follows clear formal structures.

📋 Examples:

- Qawwalī: ritual progression

(qaul → hamd → na‘at → manqabat → ghazals)

→ Strophic form with repeated refrains and accelerated jor coda - Ayin Mevlevi: 4 movements + instrumental interludes, timed to stages of whirling dance

- Līla Gnawa: thematic cycles linked to specific spirits (mlūk)

- Hadra / dhikr: escalating sequences of repetition (slow → fast)

- Fixed poetic-musical forms in some traditions:

- Andalusian nūba

- Murabba‘ qasida in inshād

- Kafi in Punjabi Sufi poetry

🎯 Common goal: to lead the soul toward ecstasy, balancing repetition and variation.

🎻 3.6 Instruments and Timbres

From a cappella chanting to full spiritual orchestras, instrumentation enhances mystical power.

🥁 Universal percussion instruments:

- Daf (Iran), bendir (Maghreb), duff (Syria, Egypt)

🎼 Signature instruments:

- Ney (reed flute) – breath of the soul in Ottoman samā‘

- Oud, rebāb – favored in Persian Sufism

- Guembri – central lute-drum in Gnawa rites

- Harmonium – essential to qawwalī (introduced in 19th century)

- Qraqeb – large metallic castanets used by the Gnawa

- Ghaita / zurna – piercing oboes in Aïssawa music

🔊 Deep sounds (guembri, dholak) ground trance; sharp tones (ghaita, ney) awaken the soul.

🎶 Monody and Heterophony:

- Most traditions are monodic (single melody line)

- Or heterophonic: same melody adorned differently by each voice

- Little harmonic polyphony: unison reinforces unity of hearts

🎯 These musical traits weave a sonic tapestry where every note, breath, and silence becomes a tool for spiritual awakening.

🧘♂️ 4. Fonctions spirituelles et sociales du chant soufi

🔮 4.1 Transe, extase et thérapie spirituelle

Le chant soufi est avant tout un véhicule vers la transe mystique.

- Dans le qawwalî, on parle de wajd : un état d’extase provoqué par la répétition et la montée en intensité du chant.

- Chez les Mevlevis, la hal (état spirituel) est atteinte par la danse giratoire.

- Chez les Gnawa, la transe vise la possession rituelle par des esprits bienveillants, en vue de la guérison spirituelle.

🎵 Le chant déclenche un état modifié de conscience où l’ego s’efface pour laisser place à la présence divine.

💬 Témoignages historiques

- IXe siècle : Al-Junayd entre en ravissement pendant le samâ‘

- XIIIe siècle : Nizamuddin Auliyâ pleure lors des chants mystiques à Delhi

✨ Effets observés

- Larmes, danse spontanée, cris, silences profonds

- Sentiment d’union avec le divin

Le chant devient aussi une thérapie de l’âme : il libère des blocages psychiques, purifie les émotions, et apporte joie intérieure.

Dans la hadra, les souffles synchronisés créent une vibration collective qui amplifie la puissance du rituel.

🕯️ 4.2 Mémoire mystique et transmission orale

Le chant soufi joue un rôle crucial de mémoire vivante :

📖 Transmission des enseignements

- Les poèmes et chants véhiculent les doctrines soufies sans support écrit

- Chaque confrérie a un répertoire propre :

- Récits de fondateurs

- Panégyriques de la silsila (chaîne initiatique)

- Résumés des concepts ésotériques

🌍 Exemples

- Les Naqshbandis chantent les Hikmet de Ahmad Yasawî en tchaghataï

- Les qasâ’id d’Ibn al-Fârid sont transmises par le chant dans les zawiyas égyptiennes

- Les Gnawa conservent la mémoire de l’esclavage dans leurs chants

🧠 Fonction exégétique

Le chant sert aussi de lecture spirituelle vivante :

- Un vers chanté peut révéler plusieurs sens selon l’intonation

- Le maître soufi enseigne subtilement par le choix des poèmes chantés

🔍 La répétition dans l’état du samâ‘ ouvre des « saveurs spirituelles » qu’une simple lecture n’offre pas.

🤝 4.3 Cohésion sociale et ouverture interculturelle

Au-delà de la spiritualité individuelle, le chant soufi est un ciment communautaire.

🧩 Renforcement du lien social

- Sessions de samâ‘, hadra ou lîla : moments de fraternité

- Participation collective : effacement des classes sociales

Chanter ensemble abolit les hiérarchies et forge une égalité spirituelle.

🌐 Exemples d’intégration sociale

- Inde : qawwalî rassemble hindous, sikhs, musulmans

- Sénégal : les chants wolof unifient les ethnies autour des confréries

🌍 Ponts interculturels et interreligieux

- Empire moghol : des rajas hindous assistent aux samâ‘

- Andalousie : échanges entre musiques mystiques musulmanes et chants chrétiens

- XXe siècle :

- Succès international de Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan

- Adaptations de chants soufis en chorales chrétiennes

🕊️ Même sans comprendre les paroles, l’auditeur ressent l’intensité sacrée et l’amour divin.

Le chant soufi devient ainsi un vecteur d’universalité, favorisant :

- le dialogue interspirituel

- la transmission du patrimoine immatériel

- la paix intérieure et collective

🎯 En somme, le chant soufi est à la fois prière, thérapie, mémoire et lien social – une voie de transformation intérieure autant que de connexion humaine universelle.

🔄 5. Contemporary Developments and Current Issues

🌍 5.1 Revival and Global Diffusion

Since the 1980s, Sufi chant has experienced an unprecedented international rise:

🎶 Festivals and Global Stages

- Fes Festival of Sacred Music (Morocco)

- Samā‘ International Festival (Egypt)

- Jahan-e-Khusrau (India)

These events bring together Muslims and non-Muslims alike around renowned Sufi artists.

🏛️ Institutional Recognition

- UNESCO:

- Mevlevi Sema inscribed in 2008

- Gnawa culture in 2019

🤝 Modern Musical Fusions

- Qawwalī & Rock: Mustt Mustt (Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan & Michael Brook, 1990)

- Mystical Jazz: Dhafer Youssef, Abed Azrié

- Gnawa & Funk: Gnawa Diffusion

- Sufi Rock: Junoon band, singer Ali Noor (Pakistan)

🎧 Sufi chant is reaching younger urban audiences through hybrid musical forms.

🌎 Western Appropriation

- Western qawwalī ensembles: Fanna-Fi-Allah (North America)

- Widespread popularity via online videos, recordings, and social media

The message of love and peace resonates strongly in a world seeking spiritual meaning.

💰 5.2 Commercialization and Authenticity

This success also raises ethical and spiritual concerns.

🎭 Touristic Drift

- Whirling dervish shows in Istanbul or Konya

- Often devoid of prior prayers or silence

- Shortened and simplified for paying audiences

⚠️ Loss of the Sacred: has the ritual become just cultural entertainment?

💿 Fixation and Standardization

- Audio recordings fix what was once fluid and variable

- Risk of decontextualization and homogenization

🧘♂️ Seeking Balance

- Presence of Sufi masters at festivals

- Explanation of ritual meanings

- Re-creating meditative atmospheres

- Educational workshops: ney breathing, Sufi rhythms

In many places (villages, zāwiyas), chanting remains first and foremost a collective act of faith, not a stage performance.

🕌 5.3 Religious Controversies

Sufi chanting remains a subject of theological debate within the Muslim world.

⚔️ Rigorist Opposition

- Ancient and modern bans:

- Medieval jurists against samā‘

- Wahhabism / Salafism: condemnation of instruments and dance

- Fatwas prohibiting qawwalī, labeling dervishes as heretics

💣 Attacks on Sufi Shrines in Pakistan (e.g., Sehwan Sharif, 2017)

🧕 Traditional Defenses

- Sunni and Shia authorities:

- Chant revives faith

- The Prophet himself listened to devotional songs and allowed tambourine use

- Popular devotion to Sufi chant remains strong despite restrictions

🧩 Internal Debates in Sufism

- Purification: remove folkloric or superstitious elements

- Valorization: embrace the festive, embodied dimension

(e.g., the Malāmatiyya path, which embraced blame and paradox in divine love)

Core issue: balancing faithfulness to the sacred with cultural openness

🧭 Conclusion

In the 21st century, Sufi chant remains a living heritage:

- Constantly evolving

- Rooted in community rituals

- Elevated on global stages

It continues to:

- Uplift the soul

- Transmit divine light

- Unite hearts

🎶 Between modernity and mystery, Sufi chant remains a song of the soul, resonating across peoples and centuries.

📖 Glossary

🌀 Aïssawa (Issawa)

A Moroccan Sufi brotherhood founded in the 15th century by Sidi Mohamed Ben Aïssa in Meknès. Renowned for its collective trance rituals combining liturgical chants, the piercing ghaita (oboe), and complex polyrhythmic percussion.

🕊️ Dhikr (zikr)

Means “remembrance.” A central Sufi practice involving the repetition of God’s names or sacred phrases. It can be performed individually or collectively, aloud or silently. Vocal dhikr is often sung and rhythmic, often leading to mystical trance.

💌 Ghazal

A Persian lyrical poem composed of autonomous couplets. Main themes include mystical love, longing, and spiritual intoxication. Widely used in qawwalī for its repetitive and emotionally charged structure.

🎭 Gnawa (Gnaoua)

A Moroccan spiritual tradition rooted in the descendants of African slaves. It blends Sufism with ritual possession. The music features responsorial singing, guembri (bass lute), and qraqeb (metal castanets), typically performed during trance nights (lîla).

✨ Hadra

An Arabic term meaning “divine presence.” Refers to the peak moment of a dhikr session when collective ecstasy is reached. By extension, it also designates the ritual gathering itself.

🎼 Maqām

A modal system used in Arab, Turkish, and Persian music. Each maqām features a specific scale, a distinctive emotional character (mystical, joyful, etc.), and its own melodic rules.

🕌 Madīḥ nabawī (amdah)

A poem or song in praise of the Prophet Muhammad. Widely practiced in the Arab world, typically performed by a soloist with a choir and percussion. Also referred to as inshād nabawī.

🎙️ Nasheed (nashīd)

A contemporary Islamic chant, often a cappella, with spiritual or moral content. Popular in both Arabic and English-speaking Muslim communities. Can derive from simplified Sufi chants, stripped of their esoteric symbolism.

🎤 Qawwalī

A major Sufi genre from South Asia, originating in the 13th century with the Chishtiyya order. Performed by a vocal and instrumental ensemble. Aims to induce wajd (spiritual ecstasy) through rhythmic repetition and poetic emotion.

🎧 Samā‘ (Sema)

Means “spiritual listening.” Refers to the ritual audition of Sufi music and poetry. Can denote a mystical session or sacred concert. Sema Mevlevi is the whirling dervish ceremony of Turkey.

🧭 Tarīqa

Means “spiritual path.” Refers to a Sufi brotherhood organized around a spiritual guide and an initiatic lineage (silsila). Each tarīqa has its own chants, rituals, and forms of dhikr.

💫 Wajd

An Arabic term meaning “mystical ecstasy.” A spiritual state reached during samā‘, marked by tears, ecstatic dancing, fainting, or a deeply inhabited silence. The soul « finds » divine presence in this state.

📚 Sources & Bibliography

Gnawa Culture of Morocco (2019)

📎 Available online at: unesco.org / ich.unesco.org

Qureshi, Regula – Sufi Music of India and Pakistan (Cambridge, 1986 / Oxford, 1995)

↪ A key ethnomusicological study of qawwalī.

During, Jean – Musique et extase (Albin Michel, 1988)

↪ In-depth analysis of samā‘, maqām, and mystical ecstasy.

Kapchan, Deborah – Travelling Spirit Masters (Wesleyan, 2007)

↪ Anthropological study on Gnawa culture and its globalization.

Frishkopf, Michael (ed.) – Music and Media in the Arab World (AUC Press, 2010)

↪ On the impact of modern media on madīḥ and inshād practices.

Schimmel, Annemarie – Mystical Dimensions of Islam (UNC Press, 1975)

↪ A reference work on Sufism, with a chapter on spiritual music.

Laisser un commentaire